Cofounder of the Black Lives Matter Movement Opal Tometi speaks to Kscope. (Photo by Angela Hollowell).

Brandon Varner – Editor-in-Chief

[email protected]

Opal Tometi, a cofounder of the Black Lives Matter movement and the founder of Black Alliance for Just Immigration, spoke to a crowd of around 225 UAB students, faculty, staff and Birminghamians during a lecture on Feb. 8.

The lecture began with a conversation between the moderator, UAB associate professor Dereef Jamison, Ph.D., and Tometi, and ended with Tometi fielding questions from the audience. During the discussion with Jamison, Tometi gave the crowd a picture of the movement’s founding.

Alicia Garza, another cofounder of the movement, wrote a love letter to black people on Facebook on July 13, 2013, the night George Zimmerman was acquitted of murdering Trayvon Martin. Garza asserted at the end of the letter that “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.”

Tometi felt a strong connection with the Martin case because of her own family.

Tometi told the audience of “literally praying” her little brother into existence, and the emotional toll that the Martin case took on her. She didn’t want to see her brother, who was around the same age and size as Martin end up as another person on the news.

Groups like BLM, The Black Youth Project, Dream Defenders and Million Hoodies Movement for Justice have all worked towards a common goal of centralizing an African-American voice of humanity and outrage in the face of seemingly frequent high-profile murders of unarmed African-Americans.

“Really we’re in a fight for all black lives. We don’t believe that there’s one exceptional, respectable person that deserves to be a leader or the one that we’re fighting for. We’re not only fighting for black men. A lot of black men are obviously being murdered, but this movement is also about black girls, black boys, black women, trans black folks, it’s about all of us,” Tometi said. “We’re of the opinion that you must bring the voices of the margins front and center and give them the tools and support they need to lead, and have a political framework informed by the margins. Once you do that you actually develop a political framework and an agenda that really speaks to the needs of all people, you’re not leaving people out.”

African Americans, and other minorities have a history of being left out. Tometi notices a pattern of political violence against the African American culture that she feels is still not being properly addressed.

“I look at things like mass incarceration, the high unemployment rate, the homeless rates, the health disparities, the HIV/AIDS epidemic. All of these things are testaments to our community that something is critically wrong with our society,” Tometi said. “Black people are 14 percent of the population and we’re still experiencing this degree of disparities. It’s telling. There are more black people in office than there ever have been and we’re still seeing the same type of disparities.”

As a second-generation Nigerian-American, Tometi honed her skills as an activist by fighting against regressive laws targeting people of color. The disparities of which she speaks are visible among the African American culture and African immigrants as well. The other organization that she helms, BAJI, grows out of her desire to protect her brother and people like her and him as well. Her work as an immigrant activist brought her to Birmingham during the deliberation process that led to Alabama HB 56 being enacted in 2011.

“I had a lot of experience working with different groups on the ground in Tucson and in Phoenix and a lot of communications and organizing work for a number of groups throughout Maricopa County,” Tometi said. “As a result, when I heard that these bad laws were being exported throughout the South, I knew that it was really important for black communities to be aware as to why the anti-immigrant agenda was also about an anti-people of color and anti-black agenda.”

Sheriff Joe Arpaio and the officials in Maricopa County in Arizona came up with the laws that led to Arpaio, who bills himself as “America’s Toughest Sheriff” on the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office website, is one of many figures that rose from a shift in policing in the mid-1980’s.

This shift in crime led to measures like the the 1986 law sponsored by the democratic party to introduce mandatory minimum sentences along with the “three strikes” policy Bill Clinton signed into law. These policies often build their results at the expense of people of color.

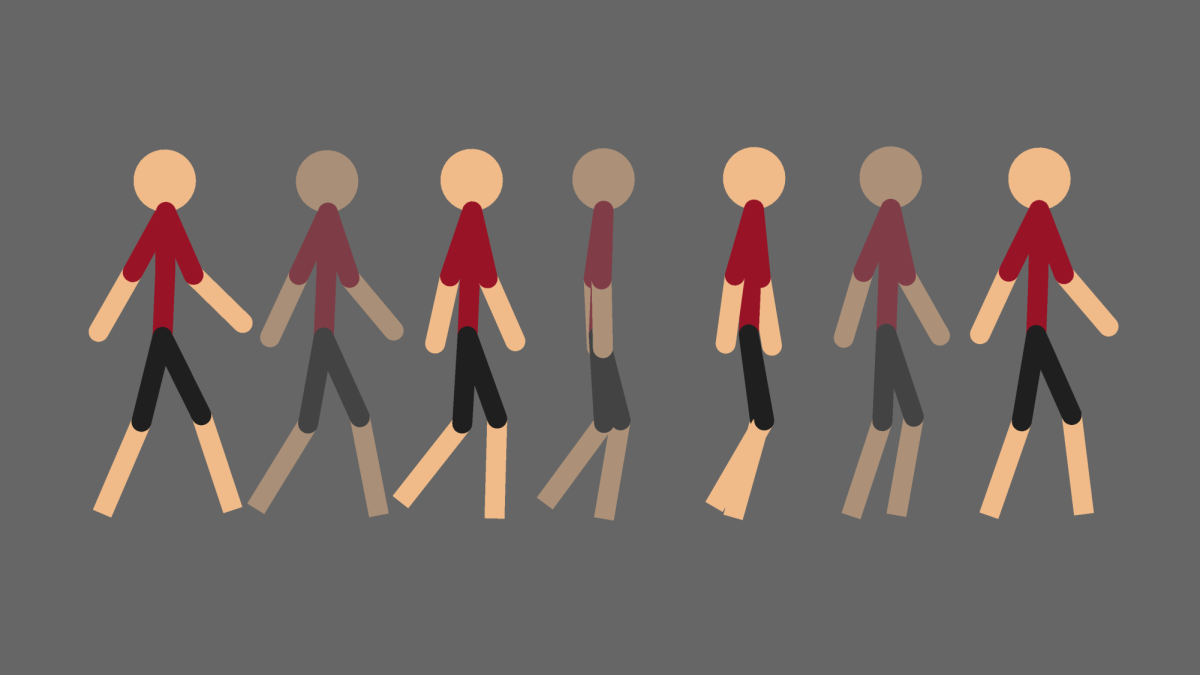

The US Sentencing Commission states that the percentage of Native Americans in federal prisons has risen by 27 percent in the past five years, according to the Wall Street Journal. Prison Policy Initiative found that Hispanics are 16 percent of the population and 19 percent of the prison population. African-Americans are 13 percent of the population and 40 percent of the prison population. For comparison purposes, White Americans are 64 percent of the population and 39 percent of those imprisoned. Though America is only 5 percent of the world’s population, it has 25 percent of the world’s prisoners, according to the NAACP.

Tometi’s initial struggle that brought her to Birmingham five years ago, informs the one that lies before her now, where she struggles to change the perception of people of color in this country.

“Why are we being criminalized as a people? Low income people, immigrants who are trying to make a living, trying to provide for their families, people of color who continue to be left on the margins or left out of jobs who experience a lot of disenfranchisement in education system and so on,” Tometi said. “Our communities are being left out of the formal economy and oftentimes forced into alternative industries if you will. That to me is the crime that is happening in our communities. So this notion of getting tough on crime, you know there are people robbing us every day on wall street. There are many other crimes like what happened with the foreclosure crisis. Many of the people that were the perpetrators of that were left to walk free. So for me, we really have to start asking questions about the real crime in our society and examining the ways that communities of color are being criminalized.”